I - Dean Potter jumps off Bute Mountain

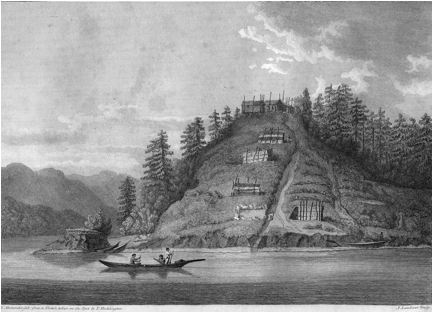

August 20th, 2011. The sea up Bute Inlet from the Homalco village of U7p (Aupe) mirrored broad-backed hills dozing like sleeping animals. As the inlet narrowed, the hills raised their backs sharply and stretched east to let in the Orford River. Pi7pknech: “little bit white at the back end” the Homalco called it and deep behind the river valley sharp peaks were still snowcapped.

The inlet narrowed again and slate-black mountains built and built in range to 6,7,8, 9000 feet until the boat cruised inland on an opaque jade surface between vertiginous stonewalls. Crystalline columns of water seemed to fall straight into the sea from a cerulean strip of sky.

Two-thirds the way up, opposite Bear River, dwarfed against the inlet’s east shore, Mike Moore piloted the motor-sailor Misty Isles up inlet with her red sails aloft. Out on the bowsprit was a madman.

Legendary free rock climber, slack ropewalker and base jumper, a man seemingly able to hover in air, Dean Potter was the focus of the National Geographic film crew Moore was contracted to transport. Co-producers Bryan Smith and Christian Begin, were to document Potter’s flight off 9219-foot Bute Mountain at the end of the inlet in a “squirrel suit” to publicize the splendor of the mountain area and Dean’s effort to break his previous flight record. It was hoped that viewers, awed by the landscape, might speak out against the unpopular efforts by Alterra Power (a recent amalgamation of Plutonic Power and Magna Energy) to obtain licenses to install “run of river” hydro projects on eighteen Bute inlet drainages and change the area forever.

Smith’s film, 49 Megawatts, showed the relative ease with which pristine ecosystems at Ashlu Creek had been turned into a gravel pit after government and entrepreneurs bamboozled distracted residents and native groups disillusioned by endless years of land claim negotiations into accepting that commercial de-structuring of waterways could produce a benign “green power.” Smith had become a keen student of how British Columbians were allowing almost anybody with a nice line of B.S to damage wilderness drainages and fish spawning sites for the production of very expensive power. He says the Bute project had arrived seven months before “like a faerie.” Bute is like that. It gets right inside some people’s heads, it stays and you care.

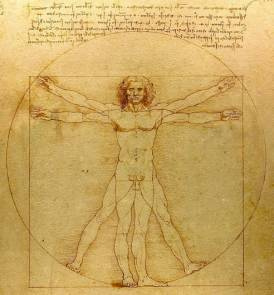

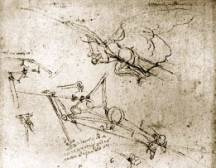

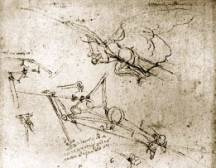

The “squirrel suit” in which Potter would “fly” is a new riff on a succession of attempts, since Leonardo da Vinci’s wooden-winged structures, to invent a way for human creatures to get off the ground, to glide and perhaps fly under their own power.

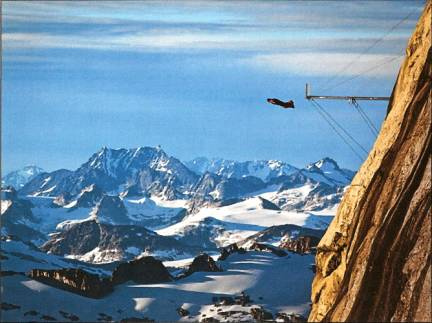

Its  name comes from the skin flap flying squirrels have between their legs that allows them to glide from tree to tree. The development of this body extension suit in lightweight synthetic fabrics has allowed the daring and supremely fit to take attempts at human flight into a new era. But, to hold the arms and legs splayed for the length of time needed for the membranes to catch enough air to turn a long free-fall into a glide takes considerable muscle and stamina. Previous “flights” have been extremely short. But Dean Potter had jumped off a stone outcrop of Switzerland’s Eiger Mountain August 2009 in what he calls a “wing suit” and stayed aloft for two minutes and fifty seconds. He dropped a total of 2000 meters into a grassy field near the village of Lauterbrunnen.

name comes from the skin flap flying squirrels have between their legs that allows them to glide from tree to tree. The development of this body extension suit in lightweight synthetic fabrics has allowed the daring and supremely fit to take attempts at human flight into a new era. But, to hold the arms and legs splayed for the length of time needed for the membranes to catch enough air to turn a long free-fall into a glide takes considerable muscle and stamina. Previous “flights” have been extremely short. But Dean Potter had jumped off a stone outcrop of Switzerland’s Eiger Mountain August 2009 in what he calls a “wing suit” and stayed aloft for two minutes and fifty seconds. He dropped a total of 2000 meters into a grassy field near the village of Lauterbrunnen.

However, those onboard Misty who’d never been up Bute were more than a little awed by what they’d undertaken when they were face to face with the raw, grey tower of Bute Mountain and the luminous, flanking wing of Bute Glacier which dominate the end of the inlet.

Bute inlet is approximately 70 kilometers long and 200 kilometers from Vancouver. It is accessible by air or water only. Logging is temporarily in hiatus, commercial fishing no longer viable and the inlet is now, with one notable exception, uninhabited. Two major rivers, the Homathko and the Southgate, drain into Waddington Harbour at opposite sides of the inlet head. The Homathko, site of an ancestral home of the Homalco people at Xwemalhkwu, where gentle Cumsack Creeks joins it, roils down from the Coast Range which tops out at 13,177-foot Mount Waddington. Below Bute Mountain, Galleon Creek joins the aquamarine Teaquahan River as it slips more quietly into the Harbour wetlands.

To get the filmmakers to the river base camp, Mike had to wait for high tide at the mouth of the Homathko and pilot Misty upriver to what is fondly called, by those of us lucky enough to spend time there, “Chuck’s Camp”. Homathko Logging Camp sits just above the 1860s town site laid out by the Royal Engineers during Alfred Waddington’s ill-fated attempt to build a mule toll-road inland from Bute Inlet to newly opened interior goldfields. This early entrepreneurial enterprise led to the only major native/ incomer conflict in the province’s history and the inlet end of the existing logging road leading upriver is laid over the1860s roadbed.

Once the tide flooded into the river, Bute expert, mountaineer Rob Wood, guided Mike up the boiling, burping, silt-laden Homathko whose opaque waters dangerously obscure the seasonally shifting sandbars and mired logs. Rob wished to facilitate the Bute Mountain film to publicize the magnificent ranges of the inlet. He and his wife Laurie have spent a good part of their lives at the mouth of Bute and climbed as many peaks as possible. Rob topped Mt. Waddington with British climber Doug Scott in 1978. His deep bond with Bute had made him desperate to preserve its magnificent alpine wilderness intact by deflecting development in the form of the threatening “run of river” hydro projects into mountaineering and eco-tourism.

Once the Misty Isles was attached to the dock Chuck Burchill had tucked into a swirly Homathko back-eddy, the crew dragged equipment and supplies up to the bunkhouse where Chuck’s wife Sheron had adorned each bed with her handmade quilts. Briefly the group could stare straight upon the sheer face of the mountain up which the flyers would free climb and off which they’d jump. Then the weather socked in for days in the way very high mountains abutting the sea can.

When Dean, fellow flyer Wayne and the crew were helicoptered to set up base camp on top of the mountain, Potter decided the project was more risky than had been anticipated. Bute was more remote and hazardous than tidy meadow-ed, ambulance-serviced Switzerland and the sheer mountain face was not sheer enough. Potter says in planning his feats he is always motivated by a recurrent childhood dream of falling and falling, of never landing, of always waking first. He grew up rock climbing and free climbing, always afraid if he entered the air he would die. Then he learned to slack ropewalk with a six-pound parachute. Now he jumps off pinnacles and peaks in a “squirrel” or wing-suit and the parachute. What he calls “my art” is about flying and landing. Falling is over. He jumps, he glides.

Potter decided he needed a forty-foot ramp from which to jump off Bute to avoid a snowy ledge too close below. Close observation of the leap of any base jumper will indicate that getting off the mountain is one thing, but getting away from it in order not to kill oneself on the very rock from which one jumped is crucial. The flyer must jump out and instantly spread the “squirrel suit” fabric with arms, legs and any other muscle they can commandeer and glide away from the rock. On the Eiger Potter had found a splendid stone diving board but here he needed a ramp. At Homathko Camp’s awesome machine shop the resourceful Chuck was charged with making a forty-foot long aluminum ramp designed by rigger Matt Maddaloni. Right now. It helps if you know that Chuck had recently built a large aluminum boat in that shed and was the guy who had singlehandedly tamed glacier-fed Camp Creek into the source of all the camp power. “Weld a ramp? Sure”. The crew spent the down time grooming a wetland swamp into a landing “meadow”.

The script called for filming Dean, and the second flyer Wayne, free climbing the sheer face of Bute, jumping off and gliding down to the “meadow”. However, to actually film an event essentially in mid-air is something else again. It is a question of where to stand or, in some cases, hang. The filmmakers themselves must be extreme athletes as well as alpine and photographic technicians, the helicopter filmers experts. A climbing film is not “real”, writing is not the event and a map is not the territory. Adventure film technique is a highly structured affair in order to give the impression of the solo traveler, climber or skier. But the athletes, the climbers and flyers in this case, still have to really climb and jump and fly. So ramp sections were helicoptered up to the mountaintop in a sling and Matt attached an anchor 30-40 feet down from the mountaintop. Then he slid down sections, attached them to each other and he and Dean lifted it horizontal. It took two tense days. The ramp projected alone from the raw grey surface like some grand and noble modernist sculpture, the cables invisible at a distance.

The weather cleared briefly. Wayne and Dean did a test drop of 1500 feet into the landing area “meadow” from the helicopter. Then it was jump time and everyone was helicoptered to the mountaintop. The flyers and photographers all rappelled down Bute’s bald face. The climb photographers had their own particular problems. They had to jumar-climb up the face of Bute Mountain ahead of Dean and Wayne who were free climbing up. They had to retrieve their ropes as they did so and film as they went. At one point one photographer had 100 pounds of rope looped around him.

On top of Bute Mountain the flyers were able to look down the inlet toward the massed Mt. Rodney, Mt. Superb and Mt. Sir Francis Drake, up the Southgate Valley, down at Galleon Creek, the Teaquahan River and up the Homathko. Then they did something so quaint, so elementary to basic science, it takes the breath away. Wing suit flyers employ an experiment proposed in the 16th century by Galileo that different masses fall at the same speed thru a vacuum. They drop a rock that gives an indication of how fast they will fall. [ii] The general wisdom is that flyers need 10 seconds to be able to jump and glide out and away from what they jump from. Dean and Wayne got 5 seconds. Dean claimed he only needed 3. Wayne, an immunological researcher has a wife and child. He declined the jump.

On jump day, the one clear day they had to film, Dean, more tired than he would have liked from the hard free climb and from the days of re-organization, walked carefully out to the mountain’s edge in his billowing wing suit, rappelled to the ramp and walked out to the far supports. For a moment he was very alone. Then Dean jumped. He fell forward with unbelievable grace spreading his arms and legs. The air buoyed his suit’s membranes and he glided out, away and down toward the monstrous crevasses and serracs of Bute Glacier. The colder air dropped him faster and he arced down past waterfalls toward Gallon Creek, deployed his parachute and landed in a 2000 feet elevation meadow, 7000 feet below the platform. It had been an approximately one mile horizontal flight. It took three minutes, a new record.

A voice from above said: “Could you do that again?” Dean got in the helicopter and jumped off the platform again.

A voice from above said: “Could you do that again?” Dean got in the helicopter and jumped off the platform again.

Chuck and Sheron at the camp said all they saw was a dot descend with a momentum the helicopter following was unable to match.

One person I told the story to said: “But you could get killed!” Oh Yes! That is certainly a possibility. However, Potter explains the risk’s appeal his own way. He says that in the solo rope-free climbs that are part of the endeavor he is at first acutely aware of being exposed and then there is a breakthrough into heightened awareness, in which he says: “I turn the impossible to the possible.” What he wants, what happens to him and for him and in him during that moment is a mystery words seldom approach. Perhaps Gerard Manley Hopkins “The Windhover” touches on that wonder.

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

dom of the daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! Then off, off forth on a swing,

As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird, - the achieve of; the mastery of the thing!

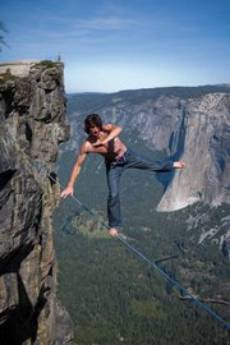

Potter is an ecstatic. He wants to reenter a zone of heightened awareness and his present incredible physical and mental ability allows him to do so. Mike Moore describes trying the slack line the film crew set up in the logging camp’s lawn, how he could manage 4 steps close to the attachment and how Dean and the others skipped around on the rope, their balance and recovery in no doubt. On the way up inlet, Potter had become fascinated by Misty Isle’s anchor chain. It has more momentum than the rope Potter often walks over canyons without even a parachute, walking it would make each step exist in an alternating arc. Oh, Yah! something new, something difficult, not just a physical challenge, but also a way to experiment with the mind. Dean is looking to see how far he can go, how much control and relaxation is needed to find that zone where everything meshes, where the art is.

And wing suit fliers want to land without deploying the small parachute at the end. But, the stress on the body of holding the suit extended pushes the body to its limits and it may not have the ability to land without breakage. They are working on that.

And wing suit fliers want to land without deploying the small parachute at the end. But, the stress on the body of holding the suit extended pushes the body to its limits and it may not have the ability to land without breakage. They are working on that.

Dean Potter speaks of what he does as “my art”. His tools, his body and mind, are at their peak. So far, once he enters completely in the act he can do all the things he needs to do at once at the moment of the jump. He is totally present. He better be. When Mike brought a load of beer up to the crew right after the jumps Dean said; “No, No thanks - Not ready to go there yet.” No. Still present. Still.

[see “The Man Who Can Fly, Behind the Scenes”, National Geographic Channel

& Friends of Bute Inlet: www.buteinlet.net/]

II Teaquahan River c. 1990-92, Sam Smythe and Bobo Fraser.

[i] Potter Bute Inlet photos by Jim Martinello.

[ii] Galileo is said to have dropped two balls of different masses from the Leaning Tower of Pisa to demonstrate that their time of descent was independent of their mass in opposition to Aristotle’s theory that a ten pound weight would fall faster that a one-pound weight. Some suggest this was more a thought rather than real experiment.

[iii] Vitruvian Man, Leonardo Da Vinci, The Canons of Proportion, c. 1487 Based on correlations of ideal human proportions with geometry described by Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of

De Architectura.

name comes from the skin flap flying squirrels have between their legs that allows them to glide from tree to tree. The development of this body extension suit in lightweight synthetic fabrics has allowed the daring and supremely fit to take attempts at human flight into a new era. But, to hold the arms and legs splayed for the length of time needed for the membranes to catch enough air to turn a long free-fall into a glide takes considerable muscle and stamina. Previous “flights” have been extremely short. But Dean Potter had jumped off a stone outcrop of Switzerland’s Eiger Mountain August 2009 in what he calls a “wing suit” and stayed aloft for two minutes and fifty seconds. He dropped a total of 2000 meters into a grassy field near the village of Lauterbrunnen.

name comes from the skin flap flying squirrels have between their legs that allows them to glide from tree to tree. The development of this body extension suit in lightweight synthetic fabrics has allowed the daring and supremely fit to take attempts at human flight into a new era. But, to hold the arms and legs splayed for the length of time needed for the membranes to catch enough air to turn a long free-fall into a glide takes considerable muscle and stamina. Previous “flights” have been extremely short. But Dean Potter had jumped off a stone outcrop of Switzerland’s Eiger Mountain August 2009 in what he calls a “wing suit” and stayed aloft for two minutes and fifty seconds. He dropped a total of 2000 meters into a grassy field near the village of Lauterbrunnen. A voice from above said: “Could you do that again?” Dean got in the helicopter and jumped off the platform again.

A voice from above said: “Could you do that again?” Dean got in the helicopter and jumped off the platform again. And wing suit fliers want to land without deploying the small parachute at the end. But, the stress on the body of holding the suit extended pushes the body to its limits and it may not have the ability to land without breakage. They are working on that.

And wing suit fliers want to land without deploying the small parachute at the end. But, the stress on the body of holding the suit extended pushes the body to its limits and it may not have the ability to land without breakage. They are working on that.