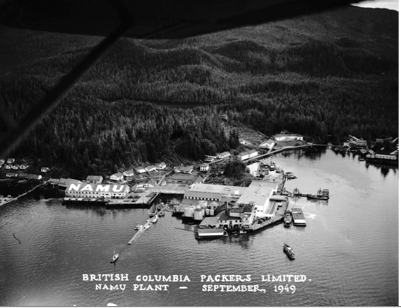

A childhood spent on Texada Island at the brim of the Pacific Lime quarry gave me a soft spot for the footprint and atmosphere of coastal industrial infrastructure. I was the wandering girl flicking a magic cast of solidified lime dust off a Salal leaf unaware of its dangerous message or that a whalebone found on a Blubber Bay beach marked the locus of an industry that decimated the Gulf of Georgia whales. My much-adored “Gramp” built kilns that burnt the limestone to make the lime that made the cement that re-built B.C. Packers’ Namu cannery after a 1961 fire. He died of lung cancer.

In the summer of 1989 Don, Liz, Wendy, Bobo and I ventured upcoast from Desolation Sound in two small boats. I’d named our twenty-foot, aluminum speed boat Tetacus after the Salish Chief who guided Spanish Captains Galiano and Valdez north in 1792. Fascinated by the magic of sails, Tetacus also learned to annotate charts for the explorers. I thought our new boat should be named for a man as curious about new technology as I was about the old.

Loosely following early explorers’ routes, we trolled up channels and crossed sounds north from Desolation and anchored at night to sleep in our boats as if they were tents. We had charts, but no phone, depth sounder, GPS or radar. At Village Island fallen wolf posts, and the fluted house uprights that rose from a haze of Fireweed, made our Northwest journey seem the cultural equivalent of going to Greece. For eleven days we avoided modern settlements.

On July 28th we edged out of Blunden Harbour to check the weather for our trip north around Cape Caution and offshore toward Spider Island. To stretch our legs, we went thru Kwakshua Channel and anchored at Pruth Bay on Calvert Island. Liz and Wendy picked berries as we walked back from the grand arc of beach we’d discovered facing the open ocean. That night we cooked a salmon caught in Hakai Pass on a Spider Anchorage beach and followed it with berry-laced bannock. A huge Northern Raven landed low on a branch to talk. After we anchored out, Bobo became violently ill and I spent the night wondering if I should start up the boat and have Don, who had navigation skills, guide me in the dark to the Namu Cannery we’d heard of. I was afraid Bobo would have to fly out but, in the morning, as Don led us east, our patient recovered. The source of his illness remained a mystery since we’d all eaten the same thing.

Once the boat was tied up at B.C. Packers Namu docks, Bobo availed himself of the free shower and I wandered through the sprawling community rebuilt after a fire had levelled the cannery established here by Robert Draney in 1893. There was now an enormous fish processing building, a sardine reduction plant and a liquor outlet with a beer-mug shaped aluminum door handle.

Enigmatic chunks of equipment were scattered near an open store. Wide boardwalks and wire-bound wooden pipes led west along the bay’s flanks to the shuttered “Namu Hilton”, a cookhouse and a bridge that crossed the Namu River to a bunkhouse and a gas dock.

The patient recovered enough for a bowl of soup in the Namu Café and we walked back to the lake that supplied the cannery power and looked for a rumored petroglyph. Returning to the cannery I felt odd: bedazzled, intrigued and excited.

Doll-like wooden buildings, with classic cannery-town green trim were set behind cement block tunnels. Lumbering dinosaur-sized metal structures teetered on pilings set into middens stuffed with clamshells, bones, rusting cable and steel bed frames. I seemed to be hyperventilating.

Did I love this or hate it? I’d lived in such small houses at Pacific Lime and loose metal siding twanging in the wind, a lonesome piece of machinery clanking its way around the bay were sounds from my happy childhood. And I’d been fascinated by middens since we turned northeast off Johnstone Straight and landed at the white shell beach spilling from Matilbi’s deep purple/brown shell-studded soil. I’d learned the seafront of a midden lied about its age when I saw a stovepipe and a porcelain cup wedged deep into the bottom of the dark mix at Karlukwees Village. After eleven nights sleeping in abandoned bays on the boat, I realized everything including my balance had become pretty fluid, but surely coastal culture was oddly re-sorted at Namu? An interface of rusted wire, petroglyph, beer bottles, Namu t-shirts, obsidian fragments and barnacled demijohns of poisonous chemicals were mixed with kelp and fish bones and infused with the intoxicating, addictive smell of plants that grow where salmon rivers meet the sea. I felt sandbagged by something I couldn’t identify.

Our friends departed to explore Goose Island further out to sea. After a dinner invitation for later from a pair of sail-boaters, we cruised 35 K north to Bella Bella where the Heiltsuk, whose village Namu had once been, came from as seasonal cannery workers. Exploration is thirsty work and we decided to have a drink in the waterside pub, but its blank stainless steel door and beer that came only in plastic glasses indicated a possibility of more action than we craved so we cruised back to Namu. It began to rain lightly and we gratefully joined the sail-boaters aboard their bigger craft. Cautioning us about two large black wolves seen just where we’d eaten our Spider Anchorage dinner reminded them of a Gilford Island potlatch. During a newly staged “Dance of the Animals”, the Wolf speaker had called out masked coastal creatures; bear, eagle, orca, raven and finally a swarm of bees, to dance. I could not sleep.

Our friends departed to explore Goose Island further out to sea. After a dinner invitation for later from a pair of sail-boaters, we cruised 35 K north to Bella Bella where the Heiltsuk, whose village Namu had once been, came from as seasonal cannery workers. Exploration is thirsty work and we decided to have a drink in the waterside pub, but its blank stainless steel door and beer that came only in plastic glasses indicated a possibility of more action than we craved so we cruised back to Namu. It began to rain lightly and we gratefully joined the sail-boaters aboard their bigger craft. Cautioning us about two large black wolves seen just where we’d eaten our Spider Anchorage dinner reminded them of a Gilford Island potlatch. During a newly staged “Dance of the Animals”, the Wolf speaker had called out masked coastal creatures; bear, eagle, orca, raven and finally a swarm of bees, to dance. I could not sleep.

Home at Desolation Sound I was unable to paint as I’d done before. I folded sheets ripped from a roll of finely striped wrapping paper into signatures for a book into which I was able to release the journey’s intense residue. That fall, still alight with the vivid sensations I’d received at Namu, I searched for archeological information about the old cannery site. Between 1968 and 1994 an SFU Archeology team made a twenty-foot deep dig behind the boardwalk bunkhouse and another at the Namu River’s mouth. A burial was found dating to c. 3400 B.C. and, after digging down to the last evidence of human habitation, the archeologists estimated Namu had been occupied for at least 9000 years.

Nine thousand years?

The mid-coast of British Columbia, stretched further and further lengthwise by our journey, now presented me with an incomprehensible depth of time. The cannery’s thin white crust floated on a timeline of human activity I’d never associated with our coast. People had been cutting up fish in Namu Harbour for nine or, as it is now thought, 11,000 years. Where 104 years of cannery time interfaced with these extraordinary millennia of native activity, the ineluctable sea rose and fell, plucking and poking organic and inorganic material in and out of the levels. In a winter storm a thousand years of fish bone and shell might collapse seaward and bury within it a bed frame pushed over its edge by bulldozer after the fire.

I have never been the same.

It’s proposed by those who study such things that the north end of Vancouver Island may not have been glaciated as long as areas north and south and sites around Namu and out to Calvert Island more continuously occupied than elsewhere. Namu, located at the top of Queen Charlotte Sound, near the south entrance to Burke Channel leading inland to Bella Coola, and at the bottom of FitzHugh Sound leading north, could have functioned as a trading hub. Obsidian and quartz for micro blades and slate for knives, material found in the midden but unavailable close by, were moved in trade loops north, south and east. The cannery had sat for just a moment atop ages of First Nations lives. Their descendants, becoming cannery employees, melded their sophisticated food system with the incomer’s commercial enterprise. The industry then peaked and waned as transportation modernized and salmon stocks declined.

The next summer I began yearly journeys through the watery coastal world. Tac was beached in front of thirty-foot middens, I photographed the rock art I found everywhere and became fascinated by an ancient, Native engineered fort and two and three level village terraces in the Broughton Archipelago. There were voyages up deep inlets under the gaze of massive mountains and I gathered glacier water to paint with from thousand-foot waterfalls. Inspection of the series of old canneries strung along the coast and the Butter clam-packed middens everywhere led to collating the unrecorded evidence of pre-historic economies of shellfish cultivation in Native-built clam gardens.

[judithmwilliams.com – Clam Gardens: Aboriginal Mariculture On Canada’s West Coast]

Whether it was a carving on an intertidal rock, red pictograph images of a fish trap on a vast cliff, or a store suspended falling forward off the Butedale Cannery shore, evidence of people at work in the landscape generated paintings, installations, photographs and books addressing the dimensions of time and space that I’d felt at Namu.

The recent Globe & Mail article about Namu cannery’s collapse led me to search online for relevant images and I found Namu, a painting I’d made in 1991 and shown at The UBC Museum of Anthropology. Like the still unbound book waiting for resolution, it was a beginning of deep respect for the coastal interface of cultures.

The recent Globe & Mail article about Namu cannery’s collapse led me to search online for relevant images and I found Namu, a painting I’d made in 1991 and shown at The UBC Museum of Anthropology. Like the still unbound book waiting for resolution, it was a beginning of deep respect for the coastal interface of cultures.