Fall, 2015

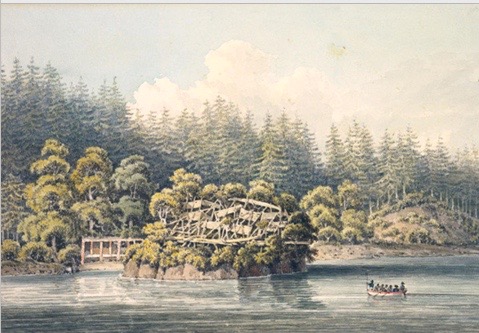

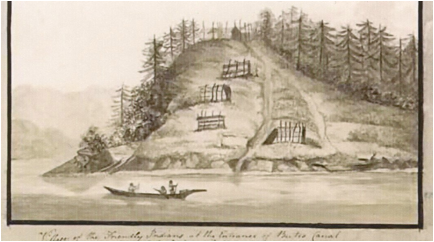

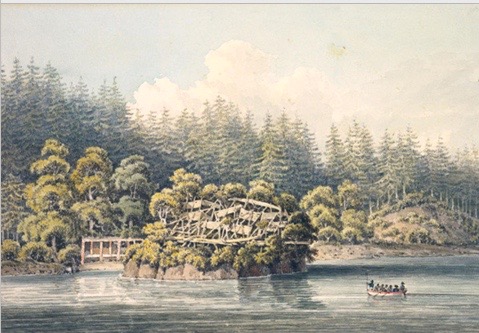

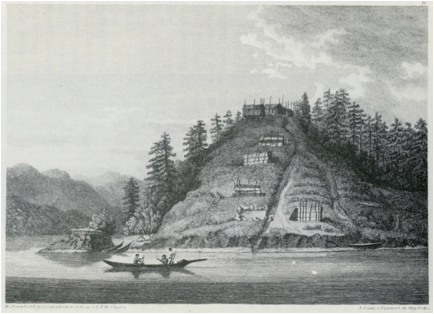

Watercolour by William Alexander

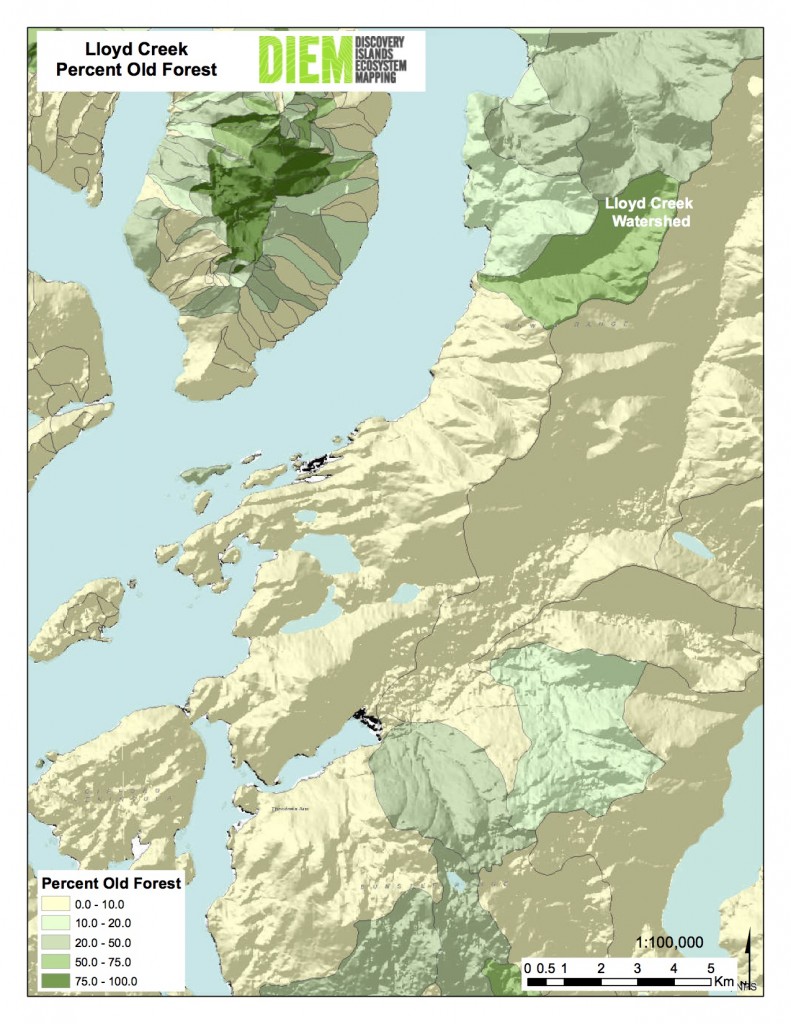

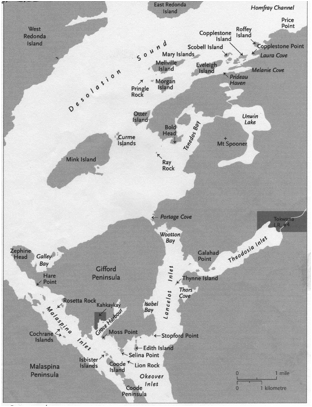

The curious name of this Sliammon /Klahoose territory village site comes from a story in “The Journals of Archibald Menzies,” surgeon/botanist aboard Capt. Geo Vancouver’s Discovery during its exploration of the West Coast of British Columbia. In June 1792, the Discovery and its companion ship the Chatham entered the area Vancouver was to call Desolation Sound in company with the Spanish ships Sutil and Mexicana commanded by captains Dionisio Galiano and Cayetano Valdes. The four ships anchored off Kinghorn Island in the Sound, but wind forced them to move to Teakerne Arm on West Redonda Island. During the period from June 26th to July 13th, Menzies and a small crew rowed, sailed and surveyed through the area in small boats. On June 30, after breakfasting on a small island covered with pines, they headed out of Theodosia Inlet where they’d spent the night and headed north:

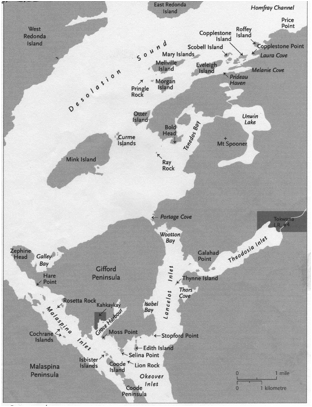

[T]o the great arm [Desolation Sound] and proceeded along shore to the North Eastward passing a large island [Mink Island] in mid-channel, where the Arm is at least a league wide. We soon rounded out a deep Bay, [Tenedos Bay] on the West side of which we saw a great number of fish stages erected from the ground in a slanting manner for the purpose of exposing the fish fastened to them to the most advantageous aspect for drying. These stages occupied a considerable space along shore and at a little distance appeared like the skeleton of a considerable Village; they were made of thin Lathes ingeniously fastened together with Withes of the roots of pine trees and from the pains and labour bestowed on them it was natural to infer that Fish must be plenty here at some time of the year, and that a considerable number of Natives rendezvous for the purpose of catching and drying them for winter sustenance, but, as we observed no huts or places of shelter for their convenience, it is probable they make but a short stay.

Fish and fish drying racks in Klahoose territory at Walsh Cove.

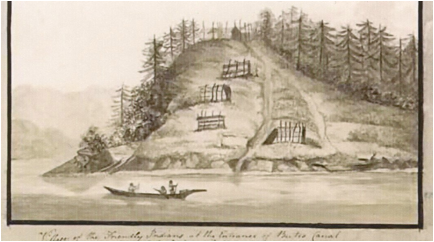

After quitting this Bay we followed the same shore which trended North Eastward and soon after passed by a narrow Channel on the inside of a cluster of steep rocky islands wooded with pines, but did not proceed above a league when at the farther end of these islands we came to a small Cove in the bottom of which the picturesque ruins of a deserted village placed on the summit of an elevated projecting rock excited our curiosity and induced us to land close to it to view its structure.

This rock was inaccessible on every side except a narrow pass from the land by means of steps which admitted only one person to ascend at a time and which seemed to be well guarded in case of attack for right over it a large maple tree diffused its spreading branches in such an advantageous manner as to afford an easy and ready access from the summit of the rock to a concealed place amongst its branches, where a small party could watch unobserved and defend the pass with ease. We found the top of the rock nearly level and wholly occupied with the skeletons of houses – irregularly arranged and very crowded; in some places the space was enlarged by strong scaffolds projecting over the rock and supporting houses apparently well secured. These also acted as a defense by increasing the natural strength of the place and rendering it still more secure and inaccessible.” [i]

After rudely riffling through the effects of what they estimated might be as many as 300 inhabitants, Menzies and the sailors were routed from the mound by attacking fleas. They ran downhill to stand up to their necks in water, then stripped to the buff and headed back to Teakerne dragging their clothes behind the boat. At the ships they stood naked in a line while their clothing was boiled free of fleas lest these saucy vermin become established onboard. This seriocomic event led to the designation of the site as Flea Village. It is now listed as a defensive site in the archeological records. Sliammon elder, Norm Gallagher, who surveyed this area with provincial Parks officials in the summer of 2005, stated it was more of a settled village than just a seasonal encampment. The explorers felt the buildings were stripped of their outer cladding and the place deserted due to the fleas, but they had no sense the local First Nations moved from winter village to seasonal camp to procure and process food and would return when appropriate. Royal Engineer Robert Homfray reported seeing Native people, in the fall of 1861, using boards bridging canoes to ferry fish down what is now called Homfray Channel. House planks could be stripped off to move goods and then side another seasonal dwelling.

The exact location of this village became obscured over time despite Menzies noting John Sykes had made a drawing on the spot. The British Admiralty required all logs and drawings to be turned over when the voyagers arrived home. A few images were worked up in watercolour by William Alexander and some engraved for the publication of Vancouver’s journals.

Beth Hill was a most energetic upcoast sleuth, ferreting out rock art locations and long time coastal residents and their stories. She and her husband Ray Hill accomplished the first organized recording of upcoast petroglyphs and their Indian Petroglyphs of the Pacific Northwest, published in 1974, is still the only extensive text on the subject. If Beth thought she knew where Flea village was, I was onboard and I boated us out of Refuge Cove across Desolation Sd., to Prideaux Haven and into the rocky bay behind Roffey Island as instructed. I slid the boat into a beach to the left of a high rock mound, let Beth off and she disappeared into the bush. I waited. Suddenly there was a scream from above: “I found it, I found it! This is it! You have to come up!” Beth materialized on the beach full of instructions how I should scramble up the backside of the rock via a maple tree. She held the boat while I pulled myself up a narrow passage at the east side of the mound. The handsome flat top was crowded with trees under-laid by the exquisite Vanilla Leaf, used by First Nations as an insect repellent, now in spiky bloom. I found a few rusted stove remnants and felt the odd moss-cloaked, rotting board underfoot, but there was no obvious sign of buildings or the bridgework Menzies described. From the front of the mound there was a clear view out into the entrance to Homfray Channel and across to the abrupt rise of East Redonda. Large Maples still grew at the back of the mound and a stream flowed down the south side. Everything announced a secure site.

Although the area is now Prideaux Haven Marine Park and crowded with boats in the summer, some years after Beth and I explored, Walter Franke went to dig clams just below Flea Village in the dead of winter. Somehow his boat floated away. Walter was stranded for several days very alone with an abundance of clams to eat and a growing concern about how to survive long term. It was only a chance sighting of smoke by Rob Smail, the only other local inhabitant, as he was running south from Doctor Bay, which led to Walter’s rescue.

The history of the disappearance of this site to general knowledge is connected to William Alexander watercolour copy of Sykes drawing being titled “First Nations village, Homfray Channel, June 1792,” with the implication it is in Forbes Bay. Another title: “Deserted Village, Gulf of Georgia” is more misleading. The situation shown in Alexander’s painting is quite clear once you enter the bay. He shows the mound and its defensive bridgework and the low flat above the beach where I first landed Beth where the house framework was. The stream is not visible but it does run very flat into the sea. Perhaps midshipman Sykes original sketch might clarify things.

The pre-photographic process of representing the coast of North America presents some interesting problems that result from the training of those who made the representations. Examples taken from the Spanish and British logs and published journals, although often accurate as to geographical placement do represent people, foliage and objects seen through eyes trained to image from within their societal norms of representation. Drawings done on the spot often went thru the hands of those not present before being engraved and published. What was published was as mediated by the techniques of their time as our visuals now are.

British Navel officers were trained to “take views” in pencil and watercolour and with Sykes, and midshipmen Thomas Heddington, and Henry Humphries making sketches of many areas during Vancouver’s voyage. The engraving of the Discovery, embarrassingly on the rocks in Queen Charlotte Sound, was based on a sketch by the ship’s First lieutenant Zachary Mudge. We are fortunate to have several layers of data with regard to the appearance of Flea Village: Menzies notes and published journals, Vancouver’s journal report, Sykes original sketch and a watercolour translation by Alexander. Slight discrepancies of image or observation resulting from the British/European conventions of narrative and representation are instructive and cautionary.

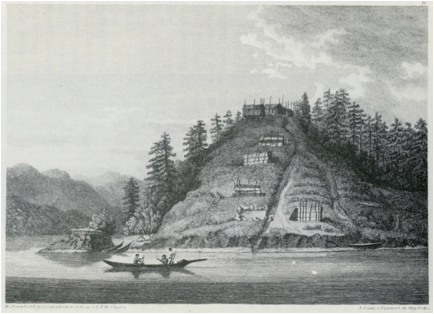

It is informative to compare the well-known engraving of “The Village of the Friendly Indians” explored later in July at the mouth of the nearby Bute Inlet with “Flea Village.” Only recently has Thomas Heddington tiny sketch emerged. It was sold in 2012 and is now in B.C.

William Alexander was hired to work up Heddington’s drawing (above) in watercolour as he’d done Sykes’ and it was then engraved for Vancouver’s A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Round the World 1791-1795. (below)

The process points out the techniques used to represent the wilderness prior to photography. The teaching of these skills was codified according to the visual canon of the time and an open-minded perusal of the original sketch is essential to get closer to what was seen. Alexander was known for his exactitude and the engraver as faithful as his medium would allow, but the hill and paths have been straightened for conventional visual dynamics and balance. Hills in the background on Sonora Island are raised. The positioning of what might be a fortified, longhouse, lookout area on the hilltop is made more dramatic, the building roofs Europeanized and 3 (?) inhabitants emphasized for “colour.” The widening of the canoe area and extension of the tidal island for balance make present site identification difficult. If, like Proust’s Grandmother, you like your images even further mediated, you can order a “handmade oil painting” based on Alexander’s watercolour on the Internet! In the case of the Spanish travelling through Desolation Sound with Vancouver, the engraving of the “Tabla” they found in Toba Inlet, published in Viage de las goletas Sutil y Mexicana, Madrid 1802, is very close in detail to a Xerox I once saw of the original sketch made of this carved panel by sailor Jose Cardero on the spot.

However, Beth was able to figure out the location of Flea Village through photographs and notes by Francis Barrow of Bertram Saulter and his friend Frank who lived atop the mound in the 30s. They hand logged, were building a boat and had a garden on the lower Native house site from which they brought the anchored Barrows a “pan of peas.” Saulter had likely been given a preemption there. Barrow was the first upcoast boater to spend his summers photographing and drawings pictographs, petroglyphs, village sites and artifacts during this period for the Royal B.C. Museum and the National Museum in Ottawa. He photographed many of the people living in the areas thru which he and his wife Amy travelled in their small, wooden cruiser Toketie from Sidney as far north as the Broughton Archipelago. Beth compiled his notes and Ray Hill restored his photos for Upcoast Summers. [ii]

There is always more to discover. If this was a long-term village site as well as a defensive one, there is likely a Coast Salish name. The Klahoose name for Forbes Bay just north is Aap’ukw’m, meaning “having maggots.” It’s said the cliff at the north entrance to the bay turns white to represent maggot eggs when the salmon are about to run up river. The Klahoose camped on the wide flat north of the river where they still have an adventure camp and they made use of the rock tidal weir to harvest the fish. The Roffey Island mound sits in the middle of a food complex from there south through Prideaux Haven and Tenedos Bay and over Portage Cove to the abundant salmon run in the Theodosia River at the village site of Tuukwanen, Sliammon ID Reserve #4. While researching Clam Gardens: Aboriginal Mariculture on Canada’s West Coast, I found a semicircular clam garden below the mound, two canoe slides and a heart-shaped, rock base of a fish weir behind Coppelstone Island south. [iii] Sliammon Elder Elsie Paul’s recent memoir[iv] tells how she moved with her grandparents right thru this territory in the 20s and 30s as food and work was seasonally available. It would be polite to at least augment the derogatory name “Flea Village” with a First Nations name.

A look at the original Sykes drawing said to be in the Hydrographic Office in Tauton, England, would help figure out the actual deployment of the boards extending and defending the mound. It was so successfully accomplished the explorers thought the local people could not have engineered such a structure.

[i] “The Journal of Archibald Menzies, Journal of Vancouver’s Voyage, April to October 1792.” Ed C.F. Newcombe, Victoria, BC, 1923 (Archives of BC, Memoir v)

[ii] Upcoast Summers, Beth Hill, Touchwood Editions,1985.

[iii] Clam Gardens: Aboriginal Mariculture On Canada’s West Coast, New Star Books, Vancouver, 2006.

[iv] Elsie Paul, Written As I Remember It.